An Open Letter About Why I Stopped Using Running Records and Why You Should Too (and what to do if you can’t)

To my colleagues that are using running records in your classroom,

First and foremost, I applaud your use of assessment to inform instruction! Our profession benefits from teachers who look at student performance and data and use that information to make instructional decisions. What we do matters and we do it better when we consider a student’s current level and needs.

Secondly, I want to acknowledge that I used running records as my primary assessment tool for years. My Master’s degree in reading was grounded in a balanced literacy approach. Heck, I even created an editable template that I sold in my TeachersPayTeachers store to make using running records easier for teachers! But as I learn and grow in the science of reading, I feel compelled to share why running records are NOT the assessment tool we need, what we should be using instead, and what you can do if your district still requires you to use running records.

Why Running Records Are NOT the Best Assessment Tool

Running records do not give us the assessment data we need to help our beginning and struggling readers. Running records are time consuming and they encourage us to analyze student errors in ways that does not align to the science of reading.

I would suspect that my argument that running records are time consuming would meet very little challenge from most teachers who actually use running records in the classroom. I remember the beginning of many school years where I needed to complete running records for 20 students, give or take. I was rarely lucky enough to guess the right starting place the first time so I could easily spend 30 or more minutes completing this assessment with each student. Add to that the challenge of finding something quiet for the rest of my very new-to-me class to do during this time, and you can see how much time this process steals from instruction.

My other argument – that the way we analyze student errors on running records does not align to the science of reading – may be less digestible to teachers who have been using running records for years and/or who are trained in balanced literacy. First, let’s look at how errors are analyzed on a running record.

Running records include an error-analysis section called MSV. In this section, teachers look at each student error and decide if they think the error was related to meaning (M), structure (S), or the visual word (V). In other words, a meaning error would suggest students weren’t paying attention to what the word means in the context of the passage. A structure error would suggest students weren’t paying attention to how the word sounds in terms of grammar or syntax within the sentence. And a visual error would suggest that the student doesn’t recognize the word and/or its parts.

Aside from the obvious problem of how subjective this kind of analysis is, two of the three categories (meaning & structure) promote strategies where students would be guessing the word based on context. From this analysis we get prompts like, “What would sound right?” and “Look at the picture”. This kind of prompting is often referred to as the 3-cueing system. These are strategies of a poor reader, one who does not attend to the letters in the word and their sound correspondences. This is a reader who guesses at words instead of decoding them.

Other, Better Assessments

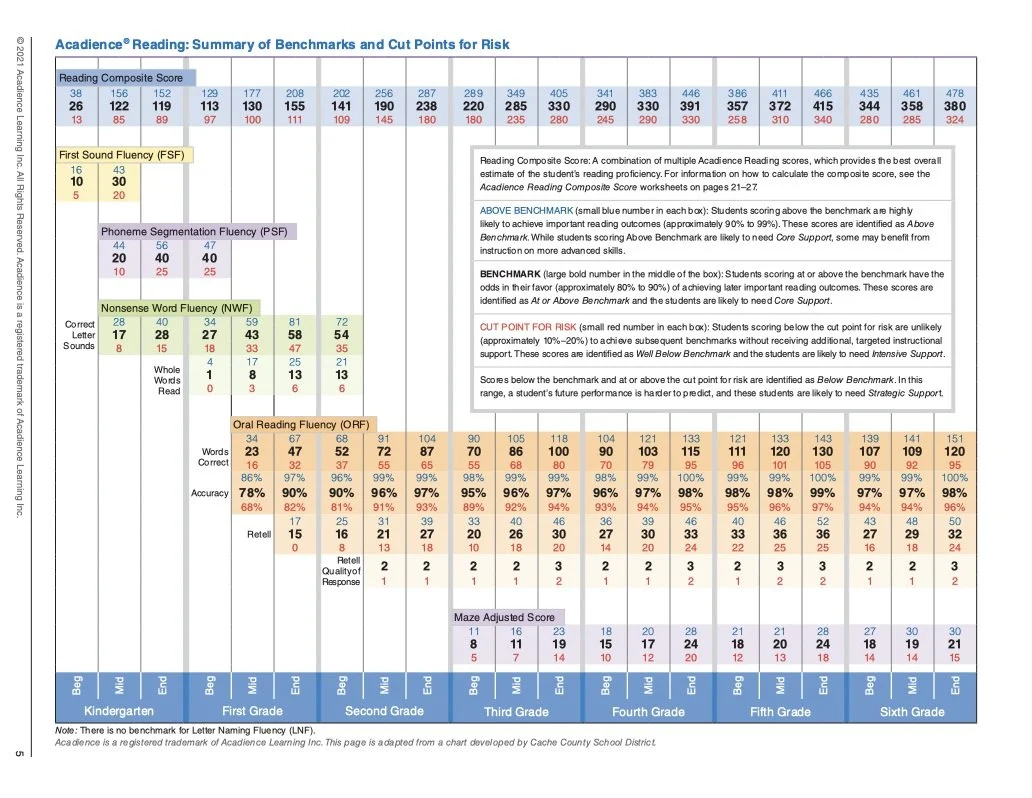

Instead of running records, I would encourage teachers to start with an assessment like Acadience Reading K-6. Acadience is a universal screener that can identify students who may have reading difficulties. Depending on your grade level, you give different subtests of the Acadience screener. These subtests will give you valuable information about how students are performing in early literacy skills.

Most important for the classroom teacher, Acadience assessment are relatively quick to administer to students and immediately help you compare your students’ scores to standardized benchmark scores. You can identify your students who are meeting benchmark and your students who are not.

Once you know which students are not meeting benchmarks, you can begin to give diagnostic assessments to those students. Diagnostic assessments, as the name suggests, are used to help identify specific areas of need for students who struggle with early literacy skills. In general terms, a screening assessment will help you identify that there is a problem and a diagnostic assessment will help you identify the specific problem.

I will organize my diagnostic assessment suggestions below around the Acadience screening assessment.

If your student struggled with First Sound Fluency and/or Phoneme Segmentation Fluency subtests, then you know that student needs support in phonemic awareness. They likely need instruction in segmenting and blending sounds in words. They probably do not need another diagnostic assessment but I would encourage you to check their progress frequently to make sure they’re acquiring these skills.

If your student struggled with the Letter Naming Fluency subtest, then you should give an assessment that identifies which uppercase and lowercase letters they do and do not know. Heggerty has a free assessment for this purpose here.

If your student struggled with the Nonsense Word Fluency subtest, then you may want to give a phonological screener, like the PAST assessment, to check on their phonemic awareness skills. You should also check their letter-sound knowledge using a letter sound assessment like this one from Heggerty. You will likely find that these students need support in segmenting and blending sounds in words.

If your student struggled with the Oral Reading Fluency subtest, then you will want to look at which component(s) of the subtest they struggled with: words correct per minute, accuracy, or the retell portion. Students who are accurate but struggle to read enough words correct in one minute likely need fluency practice. Students who are not reading accurately, should be assessed on a phonics screener, like the Core Phonics Survey or the LETRS Phonics and Word Reading Survey. If they perform poorly on the phonics screener, I would work backwards through the other Acadience subtests to see if there are problems with phonemic awareness and/or letter-sound knowledge.

If your student struggled with the retell portion of the Oral Reading Fluency subtest and/or the MAZE subtest, then their instruction should focus on comprehension. If they struggled with these comprehension subtests and also struggled with other aspects of word reading, keep in mind that their comprehension may have suffered simply because they couldn’t read the text. You may want to give students in that situation a listening comprehension assessment to see how their comprehension holds up when you have read the passage to them. You can reuse an old passage from the Oral Reading Fluency subtest. Read the passage to the student and then ask them to tell you what it was about.

All of the assessments I have suggested for you here are free online! Use the links above or search them by name. They may require some practice to administer and patience with yourself as you shift your assessment practices. But I promise you will have more informative and helpful data than you could gather from just a running record!

For My Colleagues Who Are Required to Use Running Records

If you work in a district where you have to use running records in your classroom, I sympathize with you and I challenge you to rethink the way you analyze a running record. Below I will offer some relevant information that can be “pulled” from a running record.

Pay attention to how many words the student is able to read in one minute as well as their accuracy score. Compare these numbers to the Acadience Oral Reading Fluency benchmarks for your grade level. If a student is not reading close to those benchmark scores, then you know you’ll need to use some of the diagnostic assessments mentioned previously to help pinpoint where they struggle.

If the student is reading accurately but slowly (i.e., not enough words in one minute but reading them all correctly), then you can support them with fluency activities.

If the student isn’t accurate in their reading, you can start to work through other diagnostic assessments like the Phonics screeners and the PAST mentioned previously. Also, look at the words that students are mis-reading. Don’t worry about the MSV analysis and instead, see if there are patterns to the words they are misreading.

Are there spelling patterns among these words that suggest a specific phonics pattern they’re struggling with? Are they only struggling with multisyllabic words? Do they seem to miss high-frequency words that could be a focus for instruction? If you notice patterns in these areas, you can give students a Phonics screener to help pinpoint the patterns they know and still need to learn.

Do they say the initial sound of a word and then guess for the rest of the word? This suggests that students are not attending to all the letters in each word. While a hard habit to break, it’s important to help these students with phoneme-grapheme mapping routines and explicit phonics instruction. We do NOT want to encourage guessing when reading.

You can also use the comprehension questions at the end of a running record to get a general sense of a student’s comprehension abilities.

In Conclusion

I’ve said it already but it is worth repeating – teachers who use data to inform their instruction are doing the right thing. But the kind of data we collect matters too. We need reliable data that helps us make sound instructional choices for our young readers.

My colleagues at school would likely tell you that I am a data nerd. If you’d like to talk more about running records and literacy assessment data, please reach out at readingwithmrsif@gmail.com!

Sincerely,

Hannah Irion-Frake (Mrs. IF)